🗳️ Inside Myanmar’s 2026 election

A phased vote under military rule tests legitimacy, deepens conflict, and puts ASEAN’s credibility on the line

🎯 The Main Takeaway

Myanmar began its first general election since the 2021 military coup on December 28, 2025, launching a three-phase vote in a country still fractured by civil war, repression, and unresolved political trauma.

Framed by the military as a return to democracy, the process has instead drawn widespread skepticism: major opposition parties are banned, large swathes of the country are excluded from voting, and turnout has fallen sharply compared to pre-coup elections.

🔑 Why It Matters

🧍 For people: In a country exhausted by war and mass displacement, elections still shape expectations — even when hope is scarce. A deeply flawed process risks accelerating public withdrawal from politics altogether.

🏠 For national cohesion: When large parts of the country are unable to vote due to conflict and displacement, low turnout signals political exhaustion — and opens the door to outcomes driven by coercion rather than consent.

📰 For truth and accountability: Under tight media laws and reporting restrictions, many voters receive information filtered through state control, weakening scrutiny at a critical political moment.

🌏 For the region: Myanmar’s trajectory directly affects refugee flows, cross-border security, and ASEAN’s credibility, placing the bloc’s ability to influence events under renewed scrutiny.

👀 Why It’s on Our Radar

🗳️ First election since the 2021 coup: The vote is presented by the military as a national reset, after years of direct rule, repression, and unrest — a claim that shapes both domestic expectations and international responses.

📅 Phased timing: Spanning late December through January, the three-stage process prolongs political uncertainty, keeping Myanmar’s trajectory — and external reactions — unsettled for weeks.

🌏 An ASEAN inflection point: The election unfolds as the Philippines assumes the ASEAN chairmanship, placing regional diplomacy — and the bloc’s approach to Myanmar — under immediate scrutiny.

🕊️ Post-election signals: The vote is followed by a high-profile prisoner amnesty, a move that raises questions about intent, optics, and whether concessions are symbolic rather than substantive.

🗓️ How the Election Unfolds

📌 Election timeline: The three-phase election began on December 28, 2025, with subsequent rounds scheduled for January 11 and January 25, 2026, extending the process — and uncertainty — over nearly a month.

🗳️ Early results: In Phase One, the military-backed Union Solidarity and Development Party (USDP) secured around 89 of 102 contested seats, capturing nearly 87% of available positions and underscoring the imbalance of the race.

📍 Geographic reach: Of Myanmar’s roughly 330 townships, voting is planned in 102 townships in Phase One, 100 in Phase Two, and 63 in Phase Three — leaving at least 65 townships without elections due to ongoing civil war and insecurity.

📉 Turnout: The junta reports 52% voter participation in the first phase, well below the 70–80% turnout recorded in pre-coup elections, reinforcing concerns over legitimacy and public disengagement.

🕊️ Amnesty Amid the Ballots

🕊️ Amnesty amid the vote: One week after voting began, the junta announced an Independence Day prisoner amnesty, adding a political signal to the electoral timeline.

📌 Scope of release: A total of 6,186 prisoners are slated for release, including 6,134 Myanmar nationals and 52 foreign nationals, the latter to be released and deported.

📉 Sentence reductions: Remaining inmates will see their sentences reduced by one-sixth, excluding those convicted of serious crimes such as murder, rape, terrorism, corruption, and arms- or drug-related offenses.

🕯️ Key uncertainty: It remains unclear whether political prisoners are included, raising questions about whether the amnesty represents substantive change or symbolic timing.

⚖️ What’s at Stake

🗳️ Legitimacy or lock-in: The election will either open space for dialogue — or entrench a military-dominated system behind an electoral façade.

🕊️ Peace or prolongation: A process widely seen as unfair is more likely to harden resistance than reduce violence, deepening a civil war already years entrenched.

👥 Civic space: Treating elections under emergency laws as “normal” risks further constricting space for journalists, civil society, and meaningful political participation.

🌐 ASEAN’s relevance: The bloc’s influence will be judged less by diplomatic statements than by its ability to secure tangible protection, access, and leverage on the ground.

🌏 The Regional Stakes

🇵🇭 ASEAN timing: The election unfolds as the Philippines assumes the ASEAN chairmanship, underscored by a high-profile visit from Manila’s foreign minister to junta leader Min Aung Hlaing — a move closely watched across the region.

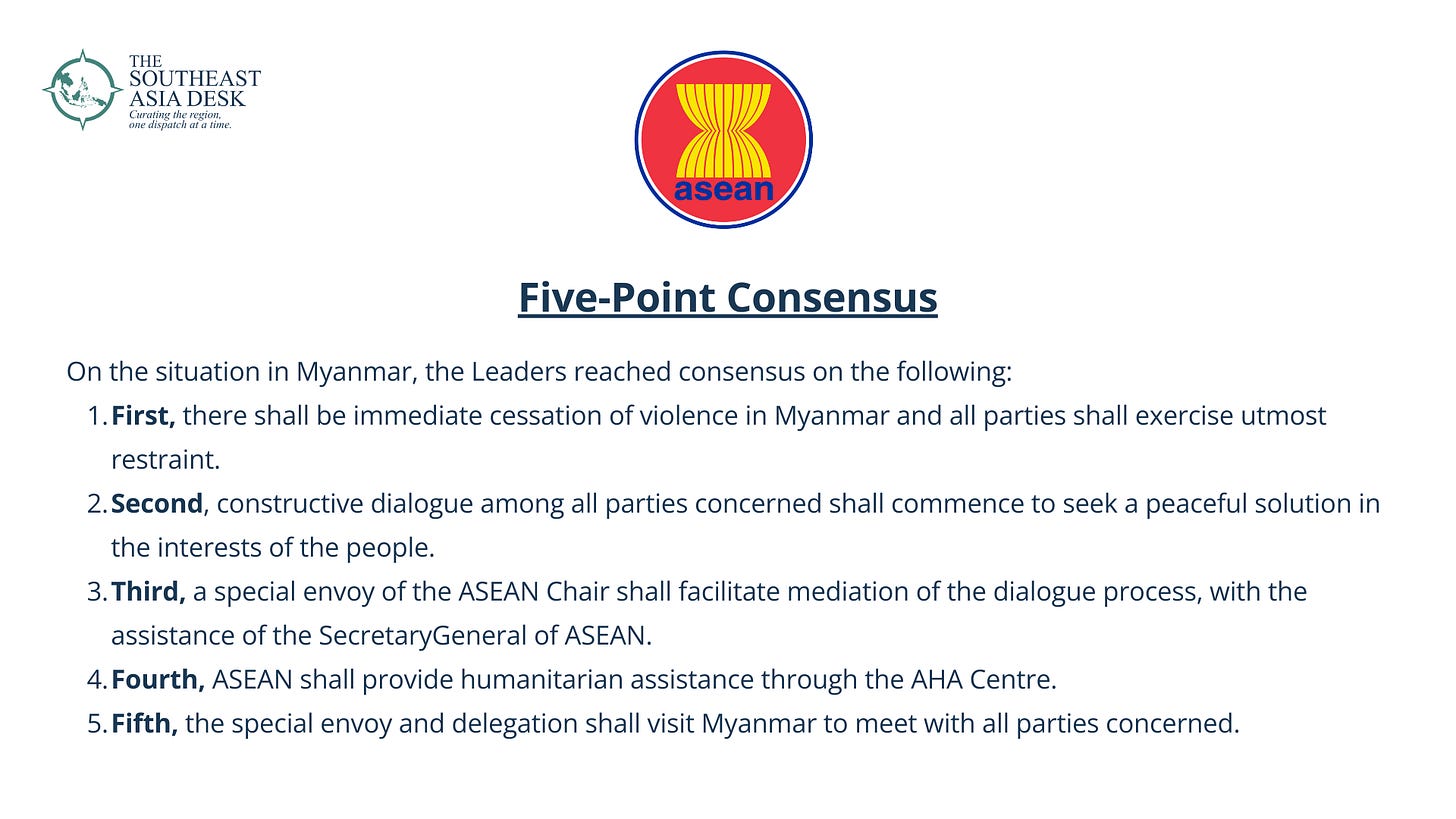

📉 A stalled framework: Despite years of diplomacy, ASEAN’s Five-Point Consensus — intended to curb violence and launch inclusive dialogue — remains largely unimplemented.

🤔 A regional reckoning: The election sharpens a central question for ASEAN: is the bloc enabling constructive engagement, or lending legitimacy to prolonged deadlock?

📸 The Big Picture

Myanmar’s current election unfolds against a backdrop of decades of ethnic conflict, repeated military rule, and only brief democratic openings — conditions that shape both public trust and political participation.

🪖 Since the 2021 coup: Aung San Suu Kyi has been imprisoned, her party dissolved, and more than 30,000 people detained on political charges, underscoring the depth of political repression.

🏠 A country at war: Myanmar is now locked in a multi-front civil war, with over 3.6 million people displaced, limiting mobility, access, and the possibility of inclusive voting.

📰 Press under pressure: Journalists operate under severe legal and security constraints, facing restrictions imposed by the Telecommunications Law, Penal Code provisions, terrorism statutes, and the Election Protection Law — narrowing public access to independent information during the vote.

“The bulk of the news gathering is done by our colleagues inside the country. We also have reporters across Myanmar, but some have had to be pulled back to Yangon for their safety as the civil war is raging in their areas. There are also domestic laws that restrict where journalists can operate and who they can contact.” — Jonathan Head, BBC South East Asia Correspondent

💔 Why This Hits Home

Low turnout is more than a statistical outcome. It reflects deep political exhaustion after years of violence, repression, and unmet promises — a signal of eroding public faith in political processes.

For ASEAN neighbours, a stalled consensus and a fragmented Myanmar mean instability does not remain contained within national borders, carrying implications for security, migration, and regional cohesion.

🔮 The Bottom Line

An election without genuine choice cannot produce peace.

As voting proceeds in fragments — across limited territory and constrained space — the defining question is no longer about the ballot itself, but about what follows: reform, renewed resistance, or a deeper political freeze in Myanmar’s future.

📰 Need More Angles?

AP Myanmar holds first election since military seized power but critics say the vote is a sham

BBC How do journalists cover a disputed election in Myanmar?

European Parliament Myanmar: Towards a ‘sham’ election - A country in need of peace, democracy, human rights, legality and humanitarian aid

Myanmar Now Few people voted in Myanmar’s junta election—and history explains why

Reuters Military-backed party in Myanmar takes lead in first phase of polls

Reuters Myanmar to free 6,186 prisoners in Independence Day amnesty during election

Reuters Myanmar junta says voter turnout at 52% in first phase of election

Philstar DFA chief meets Myanmar junta leader in first visit as ASEAN chair

Tempo Myanmar Junta Sets Final Phase of General Election for January 2026

The Global New Light of Myanmar Republic of the Union of Myanmar Union Election Commission

The Irrawaddy Looking Ahead to 2026: What Lies Ahead for Myanmar

The Irrawaddy Key Facts About Second Phase of Myanmar Junta’s Election

The Straits Times ASEAN shouldn’t end up the loser in Myanmar’s election

(BRZ/ARS)